Abdulaziz Sachedina was born into an Indian Muslim family in Tanzania in 1942. He received BA degrees from Aligarh Muslim University (in Islamic Studies) in Aligarh, India, and Ferdowsi University (in Persian language and literature) in Mashhad, Iran. In addition, he studied Islamic jurisprudence at the Madrasa of Ayatollah Milani in Mashhad. He received the MA and PhD degrees in Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Toronto. His doctoral dissertation was entitled The Doctine of Mahdiism in Imami Shi’ism: A Study of Doctrinal Evolution in the 9th and 10th Centuries.

The following interview with Professor Abdulaziz Sachedina was conducted by Ahmet Selim Tekelioglu (AT) in 2016 and presented in themaydan.com after his editorial interventions for purposes of accuracy. We hope that scholars of all age cohorts will benefit from this interview on Professor Sachedina’s life and scholarship.

Ahmet Selim Tekelioglu (AT): Thank you, Professor Sachedina for agreeing to speak to Maydan. You are a Professor of Religious Studies and a senior scholar at the Ali Vural Ak Center for Global Islamic Studies at GMU. At the same time you hold the Endowed IIIT Chair in Islamic Studies at George Mason University.

Abdulaziz Sachedina (AS): That’s right. I spent thirty-five years at the University of Virginia as a professor of Islamic Studies. But I consider myself global: I hail from Tanzania and I was educated in Tanzania, India, Iran, Iraq, and finally Canada where I got my MA and PhD at the University of Toronto in Middle East and Islamic Studies in 1976. The early 1970s were very different than what we experience today in North American universities. In the ‘70s students and scholars of Islamic and Middle East studies were not faced with so many tensions related to the hegemonic epistemology that is prevalent in the Middle East studies in the American and Canadian universities today. Although the search for appropriate approach to the academic study of Islam continues even today, following the insolvency of the Orientalist and modernist discourses that dominate studies about the Muslim “other,” and Islamic culture and tradition. The contemporary events in the Muslim world continue to hold sway for majority of the institutions of higher learning across the world.

AT: Did you start your academic career at the University of Virginia the same year?

AS: As soon as I got my Ph.D. in 1976 I was employed as a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia.

Tanzania, Iran, Iraq

AT: Can we talk about your earlier years in Tanzania? From your biodata I gather that you were born to an Indian family in Tanzania. Was that the reason you went to Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) in India?

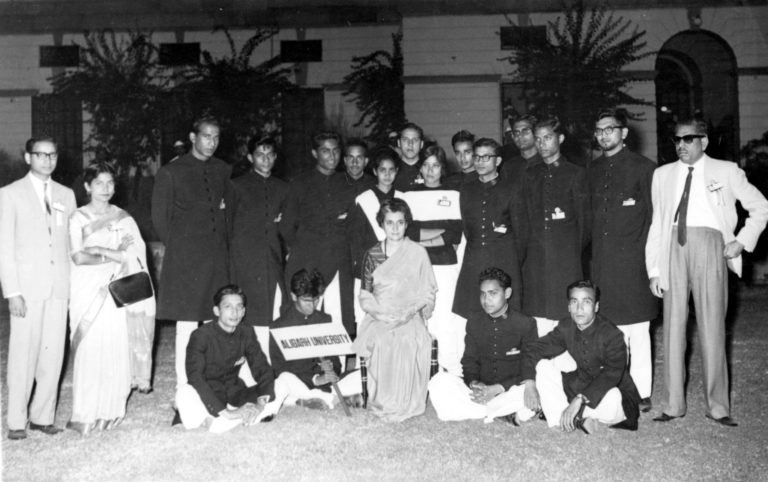

AS: Not really. So let me begin by saying that in Tanzania when I was growing up, this was a British colony. As such we were educated in the British system and I completed my high school in 1959 and I started working. I worked for Ottoman Bank for three years and then I decided to go for further education. Due to my financial situation the only possibility for me was to go to India which was cheaper than any other place that I knew for further education in those days. In Tanzania, the trend was for the rich kids to go to England, for the poor kids to go to India. I was among the downtrodden in the class stratification that was prevalent in East Africa. When you said you went to India that means they knew, “OK, he can’t afford to go to England!” But England was definitely a choice for many who could afford. I could not afford so I went to India. But I went to Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), one of the very important centers of Islamic education reform. The AMU was founded by Sir Sayyid Ahmed Khan who had visited England during the colonial period and had found Oxford and Cambridge as very attractive models of higher education for Muslims in India. So upon his return he established what was known at that time in 1875 as Mohammedan Oriental College, which in 1920 was chartered as Aligarh Muslim University. At AMU I did my B.A. General in Philosophy, Political Science, and Islamic Studies.

AT: Your interest in Islamic Studies and its being taught at AMU must have been a motivating factor for your choice.

AS: Yes it was a well-established field of study at AMU. AMU had the Institute of Islamic Studies where a number of prominent Orientalists, including Bernard Lewis and others from the English universities, had visited and had lectured. So it was a very prestigious Institute of Islamic Studies, and I was proud to have been the student of some of the best known scholars of Islamic history. Professor Maqbul Ahmed was a well-known historian of the Abbasid period of Islamic history. Professor Khaliq Nizami was another remarkable historian of India. Professor Muhammad Irfan Habib was the well-known historian of the Ghaznavid period in Indian history. I was fortunate to have studied Islamic jurisprudence and Islamic religious education with Maulana Akbarabadi, the Dean of Sunni theology; and, with Sayyidul ‘Ulama Maulana Ali Naqi Naqawi, the Dean of Shi’a theology at AMU. In other words, I had a broad education to start with. My interest was to continue to go to McGill University in Canada, because Professor Iqbal Ansari at the Institute of Islamic Studies, who had also taught at McGill, encouraged me to apply there for my graduate studies. However, again, because of my financial situation I had to give that up. As a footnote to that ambition to study in the West, I must relate that though I was almost offered a scholarship by the Aga Khan, the Imam of Nizari Ismailis, its acceptance was conditional on my conversion to Ismaili Shi’ism. For some personal reasons I wasn’t willing to do that in order to fulfill my ambition at that point. This was 1966, when I had just finished my BA at AMU.

AT: In other words, in 1966 your plans to continue your higher education were still unclear.

AS: No, my plan was to go to McGill University and study at the Institute of Islamic Studies. Professor Charles Adams was the Director of the Institute at McGill. He was the one to encourage me to apply for the Aga Khan scholarship, which meant that I would be serving the Aga Khan community once I graduated with my Ph.D. At this time, Aga Khan was determined to increase Islamic literacy in his community, and to orient his followers to learn Islamic religious practices to become part of the larger Muslim community that did not regard Ismaili community, because of their beliefs, as legitimate branch of the Islamic faith. Aga Khan was looking for training young Ismaili scholars of Islamic Studies to serve the Ismaili community. Doing a doctoral study in Islamic studies in well-known universities in the West was one of his strategies to train the spiritual leaders of the community. Since I was from East Africa, with the necessary background in Khoja-Indian community, I fitted well as a potential candidate and recipient of that scholarship – except that I was not an Ismaili.

AT: Is that the reason you decided to go to Iran? It seems there were few options for your continuation of a higher degree.

AS: Actually my mind was set to study in a Western university where I would learn the modern methodology to the academic study of religion, especially my own.

AT: How did your family react to this professional route?

AS: My family had already encouraged me because I was orphaned from the early age. It was my mother who became the guardian and the main force to encourage me to go for further studies. She was my spiritual as well as my professional guide. However, we had no family finances to support my further studies. I had applied for community scholarship and I succeeded in acquiring a small scholarship from the East African Federation of the Khoja Shi’a community. I went to India with that scholarship. It was minimal but I survived three years when I met a professor at AMU who had a PhD from Tehran University in Persian Language and Literature. We became friends and when I told him about my intention to go to McGill and read Islamic Studies, he a dvised me quite explicitly that going to a Western university without solid grounding in Islamic tradition would be a mistake. He advised me to go to Iran and get the education there so that I could go to a Western university and apply modern methodology to what I had learned in Iran.

That was a very important piece of advice, because as he said it, very accurately, “Without a proper grounding in the traditional education in Iran [and I had also made up my mind to go to Iraq], you will not be able to do original research in the Western university.” My own assessment of my needs was to immerse in Arabic studies so that my Islamic knowledge was firmly founded on the classical Islamic heritage in Arabic. While still at AMU I applied for scholarships to go to Kuwait and Medina in Saudi Arabia for further Islamic and Arabic studies. But my middle name “Abdulhussein” (my father’s name) revealed my Shi’ite birth and it became a major impediment for the Sunni countries to admit a Shi’ite student. Knowing the hard facts of the sectarian reality and accompanying prejudices in the Muslim world, Iran and Iraq were my best choices. Consequently, my search for academic training brought me to Iran. I started getting classical Arabic and Persian education in Iran. I had come to Iran from India in 1966 when I didn’t know a word of Persian. I knew Arabic reasonably well. I also learnt Hindi and Urdu at AMU. However, I had not studied Persian. The Iranian government had a cultural scholarship for foreign students.

AT: You must have started learning Arabic while in Tanzania.

AS: I had a background in Swahili, the official language of Tanzania. Swahili has some 30% Arabic vocabulary. However, it was at AMU that I studied Arabic and French as part of the program in Islamic Studies. My studies in Arabic continued in Iran and throughout my education in other places.

AT: Having no Persian proficiency when you came to Iran must have been quite a challenge.

AS: Well I was in good hands. Iranians are very hospitable people and very helpful. When I went to Iran, I didn’t know a word of Persian and I was among the three foreign students in Mashhad University. We were given an opportunity to study Persian. Two of them were from Afghanistan. Hence, for them it wasn’t difficult to learn Persian literature. But for me it was a major challenge to learn the language and its literature. I knew that if I proved myself capable of doing that I would qualify for the Iranian government cultural scholarship. After six months of doing Persian, I was given an examination in reading classical Persian poetry by Hafez and Sa’adi.

I was really moving fast in learning the language of the people I learnt to respect and love. I wasn’t married, so I had my time to myself. I could study Persian for ten to twelve hours a day, with lots of help from Iranian students without any interruptions. I saw the dedication with which Iranian students taught me their language and their culture. In the second year I succeeded to get the cultural scholarship from the Iranian government and admission to do a BA in Persian language and literature for four years. Hence, in 1967 and 1968 I studied Persian language with the help of my young friends; and from 1967 to 1971 I did another bachelor’s degree in Persian language and literature.

AT: You invested lot of time preparing yourself for your future doctoral work. After all, you had already earned one BA at AMU, and now this was a second BA in Iran.

AS: Yes, this was a second BA. While I was at the university in Mashhad I also started seminary education — madrasa education. Seminary studies were critical for my interest in jurisprudence and theology. Persian language and literature functioned as an indispensable auxiliary to Islamic studies in the madrasah of Ayatollah Milani (d. 1975). This is where I got the direct exposure to the classical juridical literature taught individually. In those days finding a right teacher for such studies was important. Some of these teachers taught in the mosque, after the morning prayers. This style of teaching was extremely conducive to forming a teacher/disciple relationship. These teachers, if they accepted to teach you, they treated you like one of their family members. They not only taught you to read and interpret the classical juridical literature; they also initiated you on the spiritual path (suluk) as your mentor. The other important feature of Islamic education in Iran is their curricular inclusiveness. It is important to note that while being a Shi’i country Iran was far more interested to include Sunni Islam than the Sunni countries offering anything in Shi’ite studies.

I often visited Sunni countries and was disappointed to find relatively zero tolerance of any materials on Shi’ite Islam. Egypt was changing in this respect. Al-Azhar and Iran had established an institute of “reconciliation” between various schools of Islamic thought, including the Shi’ite. In general, the Sunni world, with its triumphant position as the majority school of Islam, was not interested in Shi’a studies at all. It was very interesting for me to observe the ways in which a minority Shi’ite school, in order to prove its legitimacy and valid membership in the larger Muslim community, even now clings to the majority and tries to study Sunni Islam for its own benefit. The trend among the Sunni mainstream scholars was to refuse any recognition of the “Fifth [Shi’ite] school,” as the Shi’ite school came to be known: madhab al-khamis, in addition to the Four Sunni schools of jurisprudence. Iran provided me information and opportunity to study, interestingly, all the five schools of Islamic law. My Iranian professors thought that ‘Abdulaziz’ is a Sunni name so I must be a Sunni. I did not identify with any sectarian faction; but, ‘Abdulaziz’ is generally a Sunni name. The Iranian professors gave me lots and lots of training in Sunni tafsir, Sunni fiqh, Sunni usul al-fiqh, Sunni history, and Sunni hadiths, because they thought I was Sunni. At the same time, I also got from Ayatollah Milani’s madrasa a thorough training in the Shi’ite law and theology.

AT: Do you remember a time when they knew you were not Sunni?

AS: I had good feelings about the Ahl al-Bayt (the Prophet’s family) and I entertained positive opinion about the early companions of the Prophet – collectively known as sahaba. Hence, I was not a regular Shi’i who entertained negative attitude towards Sunnism. I think my upbringing in Tanzania was a formative factor in my openness. I still remember that my father would take us for tarawih prayers (the supererogatory prayers which the Shi’ites do not perform) at night in the month of Ramadan to a Sunni mosque. This practice generated camaraderie with all Muslims.

AT: For those who may not be familiar with tarawih prayers, it refers to recommended devotional prayers done during the month of Ramadan at night.

AS: It is remarkable that in the colonial period we were brought up in a more pluralistic society under the British government in Tanzania. We hardly asked questions about our sectarian affiliation. However, in Iran I realized that to ask about your sectarian affiliation was common. In Iran, even now, there are people who would ask me as to when I became Muslim. Apparently, my name did not indicate to them that I was a Muslim. But this was the Shah’s Iran. The Shah’s Iran was very different. Retrospectively, I found that the standard of education in the 1960s in Iran was very high, whether in sciences or humanities or social sciences. Most of our professors were Western educated, although they taught in Persian. They came with their degrees from France, England, and America. And those who taught Persian language and literature were among the best. I also found that a number of our history professors were educated at Ivy League schools like Chicago, Columbia, and Harvard. This training reflected their excellent approach and publications.

AT: So you were being exposed, on the one hand, in your traditional studies to both Sunni and Shi’a scholarship in the madrasah and at the University of Mashhad, and that at both these institutions the standard was very high.

AS: I was being trained by some of the world renowned professors of Persian language and literature, Dr. Gholam Hussein Yusufi, Dr. Jalal ad-Din Matini, Dr. Afifi, Abd al-Muhsin Mishkat ad-Dini. They were all high ranking professors. More importantly, Dr. Ali Shariati was teaching Islamic history. That’s when I got to know Dr. Ali Shariati and our friendship continued for a long time until he died in London in 1977. In other words, my friend and professor at Aligarh Muslim University was right about Iran that I would be working in a goldmine of Islamic Studies. Additionally, he was right about broad approach to Islamic studies in Iran because I was exposed to all five schools, four Sunni schools and one Shi’a school, in theology, jurisprudence, hadith studies. My training in Iran lasted for five years and I was thoroughly grounded in primary sources in Arabic and Persian. My transition to the University of Toronto in 1971 was marked by advanced standing. My professors at the University of Toronto were of the opinion that because I knew the languages of my classical sources I could move faster in my graduate studies. Other graduate students ended up spending many years mastering Arabic or Persian.

AT: Did you join University of Toronto in 1971?

AS: Yes, in 1971 I came to the University of Toronto.

AT: What prompted you to change your mind from McGill to the University of Toronto? Did you go to study there with a particular scholar? How did you make that decision?

AS: To make it short, I met two professors from the University of Toronto and University of Edinburgh at the University of Mashhad during a conference on Shaykh al-Tusi (d.1067) in 1967. 1967 marked the millennial celebrations of his contribution to the study of the Shi’ite jurisprudence and theology. During that celebration, Professor Montgomery Watt came from England, and Professor Roger Savory came from Canada. I had a meeting with them because I had been chosen to be a guide to these professors. My conversations led me to understand that the University of Toronto had a good program in Islamic Studies. Professor Savory encouraged me to apply for the MA and PhD at the University of Toronto. I was keen to go to Cambridge in England, where there was a scholarship in Persian Studies. I was applying for a scholarship without which it was not possible for me to study in a western university. In UK the E.G. Brown Scholarship in Persian Language and Literature was attractive. But my interest was more specifically in the history of Islamic thought; I was interested in the Islamic messianic idea, the future of the Muslim community. From the very beginning of my higher education I was inclined to search for some answers to the Muslim reformation. I was fascinated with the idea of the Mahdi, the future restorer of pure Islam. My interest was to study the idea of the Mahdi.

AT: So you eventually pursued that at the University of Toronto.

AS: Yes, but it required me to bypass my interest in jurisprudence and theology. To keep up with my original interest even now I am working on theology and jurisprudence. I didn’t do a lot of philosophy although I studied with some famous names in Mashhad. This list included Sayyid Jalal ad-Din Ashtiani, a famous professor, who has to his credit many volumes of work in theosophical mysticism. I read Mu’tazali and A’shari theology with Professor Ashtiani. I studied Qur’anic exegesis with Professor Waiz-zadeh Khorasani. I studied hadith-literature with Professor Mudir Shanechi. In other words, I pursued my studies as if my calling was known to me – without any confusion or doubt in my mind. I was looking for scholarships. Hence, I tried England because I thought that England was closer to the Middle East and I would be able to come back for my research whenever I wanted. Canada seemed far away. But finally University of Toronto admitted me and also gave me a fellowship. So that started my journey in North America.

The Iran Years

AT: Canada became your first exposure to the Western culture and educational system.

AS: No. Before I went to Canada I went to England – this was the first time I traveled to a different place. I had no exposure to the West. My elder brother had already migrated to Toronto in the early 1960s. I wanted to remain in the Middle East. I was exposed to new ideas and juridical methodologies of Iran and Iraq in Mashhad. I was already building a good zakhira, storage of information and methodologies that were known in the Middle East in the religious centers. However, as I discovered early on, these seminaries had little interest in history of the texts they were teaching. Their approach was founded upon textual studies without historicizing them. My first surprise when I started my studies in the University of Toronto was the centrality of methodology as an inseparable part of academic study of religion. In Mashhad I had often heard Dr. Ali Shariati contextualizing history and giving a fresh outlook on the state of the Prophethood in Arabia. His course was comprised of the early history of Islam until the Mongol invasion (7th-13th centuries). As a sociologist of religion Shariati’s approach to the study of Islamic history was attractive to me. Nevertheless, he was well grounded in his own culture and tradition. This connection with his Islamic-Iranian roots made him a unique interpreter of the beginnings of Islam. Unlike, other western educated Iranian professors who demonstrated a form of “Westoxication” that made their teaching less authentic, Shariati, who was also educated in France, preserved his native connections through his studies and as a teacher.

AT: I am sure our readers will be interested to hear about the signs or any tension between the traditional centers that you frequented in Iran and in Iraq, and the Shah and the secular university settings. Did you foresee any signs of the 1978-79 revolution coming?

AS: Yes, I think what I saw in my student days – and I was a keen observer of how religion was relevant or irrelevant in the society, I found that Iranian society in general, although religious in the sense that the culture was religious, was moving away from “established”, traditional religion and getting more and more Westoxicated. Pop culture, movies, Hollywood, all those things had an impact. My observation was leading me to panic sometimes because there was disconnect between the traditional centers of learning and the university. The university had now a faculty of theology (ilahiyat), which was established for the first time in the 1960s in Iran. Some of the traditional scholars were already teaching traditional religious sciences, including philosophy, in the university.

However, Islamic religious sciences in the form of ilahiyat were directly imported from the madrasah to the university with an emphasis on modern methodologies. The Shah’s educational plan was to neutralize the power of traditional centers of learning by offering an alternative to the traditional-modern academic study of Islam. So the new faculty members in Islamic studies were not necessarily the traditional scholars, who taught Islam. Dr. Shariati, for instance, was modernly educated Islamic scholar. This was new in the faculty of Ilahiyat. Now Ilahiyat had professors who had doctoral degrees in Islamic studies from the West. In that respect, something new was happening, namely, that religious subjects that were at one time under the domination of the ulama themselves, were now being taught in the universities and were somehow challenging the traditional methodology that did not bother to contextualize texts historically. That was a fundamental change. Should one contextualize the text? The moment you contextualize the text, you make the text product of the time and place, and consequently render its substance relative. The madrasah studied the texts without anchoring them in the history. You never asked: “When was the text published?” or “Under whose patronage?” Such questions were irrelevant when you studied in madrasah. The prevalent method was and remains up until now was based on textual studies in which you would open a text, and read it with your teacher who commented upon it. He would teach you how to read, understand, and interpret it; but discussions about the historical context were beyond the scope of madrasah curriculum. The university was moving in a different direction. The history of the Qur’an was now approaching the Qur’an not only as a divine revelation, but also as a historical/literary document. Historicism was already a source of major tension between some of the traditional scholars and the new Islamic Studies professors in the university.

AT: From all that is coming out of Iran in the field of Islamic studies today, it appears that these are some of the themes that still continue to be debated.

AS: Yes, we continue even today, because Iranian scholars like Abdol Karim Soroush have raised controversial issues about the development of juridical studies. However this rethinking in the context of modernization of Islamic thought had already started with Shariati. There were responses and refutations that were being written on the works of Shariati by the ulama. Shariati’s view of the history or the life of the Prophet was firmly founded on academic and critical study of the primary sources. His study did not follow a traditional view of the Prophet as an infallible leader — as a perfect leader, who guided the community under the divine inspiration and the divine revelation. At the personal level he might have regarded it as part of his faith because Shariati never disrespected the Prophet or any of his early followers. But what was new was that if you do not understand the culture of seventh century Arabia, you do not understand the Prophet. If you do not understand the poetry in the period of Jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic period), then you do not understand the language of the Qur’an. Secular subjects like grammar and literature were always taught in the madrasah to train students to understand classical texts. As a jurist, besides receiving training in the religious subjects related to the Qur’an and Hadith, you studied the Arabic grammar, the Arabic literature. That was the only way one could understand the legal texts. Madrasah curriculum was in a way a comprehensive study of the language, lexicographical issues with the new terms that the Qur’an was introducing, and the nuances of the Qur’an. Even in jurisprudence, study of secular subjects was part of the traditional curriculum; but it was never compartmentalized the way the university was trying to do.

After the Iranian revolution in 1978-79, it is important to state that the Ilahiyat curriculum in the university does not differ greatly from the madrasah. Pre-revolution curriculum was to encourage modern critical methodology in Islamic studies. However, post-revolution Ilahiyat does not engage in the critical study of the sources. The paradigm that the Shah had in the university Ilahiyat was the type of study that Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s scholarship exemplified. Nasr, who had obtained his PhD from Harvard University, was one of the promoters of the Shah’s program in Ilahiyat. Another great scholar in Ilahiyat in those days was Ayatollah Murtaza Motahhari, a reformist and active member of the Revolution Council in 1978-79. The Shah’s government under the guidance provided by Nasr and others like him made those decisions to include philosophy and other subjects that were otherwise neglected or were not studied in the madrasah or in the Sunni countries. I think it was remarkable that some of the prominent traditional scholars were in favor of making the madrasah education relevant to the modern society. There were others among the religious establishment who remained opposed to it because they thought that their already weakened authority would be further diluted as modernity took over the entire field of humanities. Let’s remember that the ulama in Iran knew that they had a lot of prestige and accruing authority because of their religious learning and control of juridical information on orthopraxy in the Shari’ah. In addition, Iran was a Shi’a country where the ulama were financially independent of the Shah’s treasury, because the Shi’ites pay khums (one-fifth), which is twenty percent of their gainful earnings, to the ulama for the propagation of religion and for the support of the religious institutions. Whereas in the Sunni world the religious institutions were and still remain under government control, in Iran, because of the financial independence of the ulama, who received the pious donation in the form of khums and who managed the religious institutions from these donations, the Shah could not control the madrasah.

AT: And yet, some ulama were supportive of the idea that the madrasah had to become more relevant to the modern society.

AS: Absolutely. In a way, modernly educated professors of Islamic studies like Shariati started the debate about the role of modern thought in the interpretation of traditional sources and traditional religious epistemology. Basically the modernist message was that what the ulama are teaching is irrelevant. They are teaching about what is permissible and what is forbidden in the Shari’a, and how to perform religiously required rituals. In contrast, living in modern times meant that there’s something more to life in the world today than orthopraxy. Shariati’s university students included the madrasah students too. These traditionally educated seminarians were his ambassadors in the traditional centers of learning. They were taking what Shariati taught as part of his “Islamology” (islam shinasi) back to the madrasah, recounting his new ideas to their traditional teachers. Some agreed, and some others felt threatened by this modern approach to scared knowledge over which they had monopoly thus far.

PART-2

Islamic Studies and the Idea of Mahdi

AT: Your transition to Toronto in 1971 must have been intellectually tumultuous. On the one hand, you were exposed to the traditional Islamic education; on the other, newly appointed professors of Ilahiyat were embarked on the modern Islamic studies. When you entered U of T as a PhD student you were enrolled in the courses that Canadian professors taught. How did you find these teachers at U of T? Did they have a good grasp and understanding of some of these debates that you had experienced in Iran?

AS: Let me trace back my steps a little and tell you that I had a scholarship to continue my PhD in the University of Tehran, but I turned it down. Five years in Iran (1965-71) had taught me a lot about Persian language, literature, Islamic Studies, the way Shariati approached these subjects, and the way the traditional scholars, the Ayatollahs, approached them. I was exposed very broadly to the study of Islam — both the academic study of Islam and the study of Islam as traditional authorities taught it. I turned down the opportunity to continue my doctoral studies in Tehran, because I was afraid I would not be exposed to the methodology about which Shariati used to speak in his courses. Dr. Ghulam Husain Yosoufi, the professor who taught the history of Persian literature, also used to speak about modern literary criticism and its impact upon classical heritage in the class. Moreover, there were others in social sciences who also explained their methodology in their courses on sociology and psychology.

On different occasions they spoke about the academic study of Islam and how different it was than the way it was studied and taught in the traditional centers of Islamic learning. Obviously, I had two options: either to continue my traditional/modern studies in Iran and pursue my calling as a teacher and a lecturer for the Muslim community; or, go to a western university to pursue research and teaching in modern academia.

AT: If you had chosen the first option, would you have stayed in Iran or have gone to Iraq?

AS: I would have preferred to go to Iraq because the learned jurists in Iraq were more reformist and forward looking at this time in early 1970s.

AT: Let us come back to your main interest in messianic thought in Islam and your take on it.

AS: Yes, I was more interested in messianic thought. I undertook journeys to Jerusalem, to Karbala, Iraq, expecting to find my savior. I am very serious about this! This was my intense personal side; I was fascinated by the idea that there was someone who will come to save humanity. Since the hadith-reports were talking about Jerusalem, the place where that future Imam would start his mission and then proceed to Mecca, I was keen to pursue that path in my long sojourns in those places. The messianic literature had an enormous impact on my imagination and my personal quest. My personal sensibilities were convinced that Muslim reformation would come through a revolution of a divinely appointed Mahdi (divinely guided). I used to spend time in Masjid al-Aqsa; I spent weeks in Karbala, in Kufa in Najaf, because there were many traditions that spoke about the Mahdi’s revolutionary journey that would start from Karbala, through Kufa, onward to Jerusalem, ending in Mecca. I was still unmarried, and hence, I could go around freely. I could stay in dangerous places. During the 1967 Arab-Israeli war I was in Damascus and, then in Beirut. It did not matter to me very much. What mattered was to experience everyday life in all these places, search for scholars, library resources, with a single purpose in mind: Perchance I might find a rare manuscript describing the coming of messianic Imam al-Mahdi, which I would publish for all those who were awaiting the emergence of the Mahdi.

This was truly rihla – a journey in search of religious knowledge. This was an essential part of my personal quest which was an academic study of religion. It comprised of my ambition, which, I quickly realized, could be fulfilled only in the West. I had pondered about it for a long time. My search for religion and religiosity in the community was quenched by my years spent in Iran and Iraq. I went to perform the hajj in 1964 when I was very young. Also to keep myself pure and clean, I got married early so that I do not fall in sin. It was part of my own personal understanding of what it means to be a Muslim, that I decided to get married.

AT: I am, leading you to some digression because I know our readers would love to hear about your experience in North America. Did it somehow resemble the impressions of Sayyid Qutb who wrote about America when he came to America.

AS: No, my experience was different. I was in humanities and social science and my approach to North American academic environment was one of learning and equipping myself with a rational epistemology. I was convinced that I needed to master modern method for the academic study of Islam. That was something to which I was committed. I regarded the new approach to be a key to reform and changes we were seeking in the Muslim community. I am talking about the 1960s when things were really moving fast. Early in the 1970s, the changes to our approach to understanding and approaching studies about religion were coming so fast that it was obvious that we could not hold onto the tradition uncritically.

AT: A number of revolutions, such as the sexual revolution and everything related to political and social upheavals were unfolding in every part of the world.

AS: Yes, the 1960s and 1970s were ushering the new period that would unfold in the early 1980s. Dr. Ali Shariati had a very strong influence on me. Having come from the third world country, I was not a Westerner. I was not westernized. I was not Westoxicated like Iranians were. So there was something authentic about me, and Shariati loved it. He would talk about me wherever he went, saying that we have this student from Tanzania who had not abandoned his native identity. “Isalat” in Persian means one’s essential character has not changed because of Westernization. In other words, I was not Westoxicated and Shariati respected it.

Dr. Shariati had returned from France and understood Western culture and education very well. He was authentic in his analysis of Europe. Moreover, he had studied literature and was deeply committed to his own rural Iranian culture. His classes were an antidote to the “imperialist” education that I had received back in Tanzania in the British system. Clearly, through British education we were thoroughly “Anglicized” and knew very little about Africa or Tanzania. Ironically, we were left with an inferiority complex generated by the English education that we received. After all, it was the colonialist nurtured educational system that British had created for us. In those days it was obvious that unless one gets an English education, one could not fit into the bureaucracy of the British. After completing my high school diploma I worked as a clerk at the Treasury Department. Within few months I changed my job and started working for a bank. But the bank job or earlier job at the Treasury Department did not satisfy my long term ambition to study Islam in a university.

Context, History and Classical Studies

AT: At this juncture, it will be good to return to your passionate interest in the idea of future restorer of Islam, the Mahdi. Our readers would like to understand the reasons for your dedication to the idea of Mahdism which became your doctoral dissertation.

AS: It was very controversial subject, with lots of ambiguities in terms of the primary sources which I had to investigate to fully develop my doctoral thesis. The hazards related to the sensibilities of the community over the subject of a highly developed doctrinal apparatus became the source of the condemnation of my specific research by the Shi’ite communities in North America. I had overestimated the rational and logical capacity of the Shiite community in America to which I had belonged and whom I had served for a number of years as a teacher and practitioner of my faith that was firmly founded on my deep understanding of the sources of Shi’ite tradition.

AT: This could very well explain why you chose to study the subject at University of Toronto.

AS: My professors at University of Toronto were orientalists whose methodology was based on philologically understanding the classical Arabic and Persian sources in their social-political-cultural contexts. They were profound in their analysis of the primary materials which I had to investigate as part of my graduate studies. For instance, Professor George Michael Wickens, a specialist in Arabic and Persian primary sources, was my professor in Arabic and Persian. I also started studying Ottoman Turkish with Professor Owens – an Ottoman historian. I did not pursue Turkish studies very diligently. As a graduate student you had to acquire a comprehensive understanding of Islamic civilizations based on its primary resources. Hence, history of the Safavid Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and Moghul Empire, was required of all graduate students in Middle East and Islamic studies. .

AT: Is it, then, correct to assume that your search for methodology in Toronto included textual-historical studies. Was this the method that was closely identified with Orientalism?

AS: Yes, I started taking courses in history, because I knew this was the key that I needed to unlock the contextual dimensions of the Islamic culture and religion. Historical approach enabled me to understand some of the social laws that are operative in the interpretation of our texts. In other words, anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies were inter-related in historical-textual methodology. To enhance my comprehension even more thoroughly, I took courses in the interpretation of primary historical materials and their translation into English. History became my passion, and I enjoy history even now, but I never paid attention to the operative methodologies. My professors were keen to see a major transformation in my study of Islam as an “outsider.” They required me to read several secondary sources written by excellent Muslim historians. I read M. A. Shaban’s books on early Islamic history. This was the time when I started reading the monumental study of Islamic civilization in three volumes by Marshall Hodgson. I read on my own works written by Montgomery Watt on the life of the Prophet and on Islamic religious thought. My teachers at the University of Toronto were the best I had encountered in my transition to a western university. They were, at times, hard on me because they knew about my religious commitments. I was becoming aware of the discrepancies in the texts about my faith and the difficulty of maintaining objectivity in my research. I still recall my professors totally rejecting my defensive approach in my papers; and sympathetically helping me to engage in necessary scrutiny of my sources and identifying a “development” in the creedal statements that became crystallized as doctrines in the community.

AT: Shall we say that you were still laboring under the traditional methodology that is prevalent in the seminaries in the Muslim world?

AS: Yes, and that was a source of anxiety both for me and for my professors: They respected my faith and admired my knowledge of the primary materials. But they were critical of my apologetics. They found my papers tendentious and they found my conclusions biased. They continued to critically evaluate my progress and they made me rewrite my submission several times before they would grade it as an ‘A’ work. These were British professors and they were coming with a degree from Cambridge, Oxford, and University London. University of Toronto had gathered some of the brilliant minds from UK.

AT: Was this a tension created between an “insider” and “outsider’s” approach to Islam? As you know that there is a tension that can be observed even today among scholars of Islamic/Middle East studies. How does one resolve this dichotomy?

AS: As I see it with a hind sight, it was more cultural warfare and exchange about “authentic” Islamic thought. Could there be one pure Islam, the way the “insiders” were used to speak; or were there many “Islams,” the way the “outsiders” were explaining? The tension continues today. The benchmark of academic study of any religion, including Islam, is to relativize its substance to a historical variable, without any claim to categorical truth and exclusionary salvation. In contrast, the seminary treatment of any religious tradition is founded upon absolute claims and exclusionary salvific efficacy of their own tradition.

Western scholars of Islam, in most cases, did not treat Islam as a religion in possession of divine revelation and other supernatural sources to validate its exclusive claims. In fact, western studies of Islam treated Islam as a civilization, as a culture. This is a critical differentiation in the “insider-outsider” approach. Nevertheless, my academic interest was more deeply in Islam itself. My main interest was in the question as to how Islam as a religion was adjusting to the socio-economic environment, including political environment. In other words, my academic interest as an “insider-outsider” was broader than my teachers’ narrowly defined “outsider’s” interests. For instance, Professor Roger Savory wrote about Safavid Empire and his study was a political-economic history. Professor Juwaida Cox taught history of Iraq, and her contribution was in the area of social-political history, rather than dealing with religious ideas in Iraq and how they operated in the Iraqi social universe. Indeed, as historical studies about Middle East in general, there was more interest in dynasties and how the economic and political situations influenced the overall flow of events, for instance, in the Ottoman, the Safavid or Moghul Empires. It was very interesting perspective, because at U of T you saw Ottoman Empire in the context of both Middle East and European history. To be sure, interests in modern histories of the Middle East regions were providing me with a link to the classical texts that I knew very well. My research was improvising the missing link that I could not see in economic-social-political histories of Iraq or Iran. More specifically, the missing dimension that I was interested in pursuing in my research and scholarship was the contextualization, the counter-contextualization, and the inter-contextualization detected in my textual studies. The training that I received in the University of Toronto opened my interest in such a way that, for example, that I started reading the history of Tabari, a Sunni, and compare it with the history of Mas’udi, a Shi’ite. The comparison enabled me to comprehend the tension that I saw in their approach to sensitive topics related to the succession of the Prophet. In the final analysis, as my research became deep into these early accounts, I realized that history was never meant to be categorical. The inherent relativity of the interpretation of these sources was an exercise in humility that was demanded from someone like me – an “insider” with claims of absolute truth.

In other words, juxtaposition of controversial materials, on a specific period provided me with very important links of reading theological texts. For the first time they made me aware that when al-Ashari (tenth century) was writing his theology he was under the patronage of the Sunni government. And he certainly saw a link between what he was teaching about theology and what the rulers wanted to do with Sunni theological adherence. You cannot read theology without connecting it to the historical context. To put it differently, what the western scholarship intended to teach was that one cannot read, for instance, Mulla Sadra, a great Shi’ite philosopher, without understanding the Safavid history, and the interest the Safavid rulers took in Shi’ite tradition and its scholars.

To remind our readers, let me juxtapose this method with the traditional method that was prevalent in Iranian seminaries. There it was a given that one does not have to contextualize religious texts. Hence, pedagogically, I was in search of history books written during the same period when theological texts were written. Nizam-ul Mulk’s Siyasat Nama, as I had concluded, cannot be understood if you do not understand Malikshah, the Saljuki king’s religious and political policies. And if you do not understand what Malikshah appears to be expecting from Nizam-ul Mulk you will not understand the reasons Nizam-ul Mulk is so much afraid of the Batiniya Shi’ite sect. This was the period of ascendancy of the Nizari Ismailism and its threat to the wellbeing of the Sunni world. It was threatening Baghdad, the caliphal capital. Consequently, if you do not understand the threat posed by Nizari Ismailism to Sunni establishment, you will not understand why Nizam-ul Mulk was worried about Batiniya. Why does he say they should not be employed in the court? Obviously he knew that if they were employed in the court they would work against the Sunni government. All these topics were part of, for example, another history, Tarikh-i Bayhaqi. Bayhaqi was Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavid’s historian. I was introduced to this important history in Iran as a piece of literature. Now, Ghulam Husain Yusufi, who used to teach this text in his literature class, used to contextualize it to provide rare interpretations about the author’s motives. What I learned in these courses was about the principles and rules that you follow in comparing and in contextualizing the text. One had to find the contemporaries of the author you were studying who composed their texts with substantial differences from the text under investigation, to enable you to compare these with your text. This was the best way to gauge the significance of one’s research.

Method and Doctoral Dissertation

AT: Would it be correct then to assume that this was basically the method that you followed in your work on: “The Doctrine of Mahdiism in Imami Shi’ism: A Study of Doctrinal Evolution in the 9th and 10th Centuries”? This book is an expanded version of your PhD dissertation. Is that correct?

AS: That is right. Keep in mind the word “evolution” in the title of the book. In religious circles, more particularly, among the traditional scholars, this term is offensive. The term “evolution,” according to the seminarians, smacks of materialist Darwinism. The seminarians believe that religion and religious creed is divinely given. All the beliefs and doctrines are, as the seminaries teach, divinely inspired and ordained. In other words, to use tatawwur or tahawwul in the context of the traditional sources, is not only innovative, but also a distasteful. It cannot be applied to the religious text. It’s like saying, ‘There is a history of the Quranic text!’ The Quran is not collected in chronological order; hence, one can detect different parts of the prophetic life in the Quran if one begins to understand the circumstances of its different parts. Such a view could lead to radical interpretation if one maintains that the text of the Quran can be historicized. University of Toronto, then, was an opening for my intellectual development. Consequently, when I wrote my dissertation I was worried about the negative reaction that could emerge in the community. In a way my approach was encroaching upon the boundaries of faith and moving it into the world of critical evaluation of the development of the doctrine and dogma.

AT: I am sure you were traveling back to Iran at the time because you were a graduate student. Were you engaging in conversations about this with other scholars? Was there a mentor, or someone with whom you could discuss these boundaries between faith and history?

AS: I spent a whole year in Iran doing research in 1973-74. I met and spoke to various scholars about my project. I had some good teachers, very forward looking and very forward thinking. But there was also a boundary that separated me and them. And that boundary was unsurpassable. I was determined to avoid hypocrisy in the matter of my own faith. It would have damaged my spirituality and a sense of morality irreparably. And yet, I had to be cautious in presenting my understanding of the contextualization of the texts I was reading. I would, for example, ask a provocative question regarding the sources written during the period when, according to a number of Shi’ite sources, the 12th Imam went into occultation (874 CE). My question was about the chronology of the primary sources written during this period of occultation, which lasted for some 70 years. My first question was: Do we have any records or texts preserved during that time that spoke about the occultation as understood in the later works?

Or, my follow up question was, whether most of the sources were written in the later period during the post-occultation. In other words, my search was to locate the texts that explained the philosophy and reasons for the occultation from ninth-tenth century. Most of my interlocutors were silent on the issue of chronology of the sources dealing with doctrinal issues going back to the early period between 874-932 CE. I found my own teacher, Sayyid Fazel Milani, who had relocated to Iran from Iraq in the 1970s, as one of the most enlightened and rationalist scholar of Shi’ite theology and law. We discussed, for example, the writings of the very prominent Shi’ite scholar, Shaykh al-Mufid, whose books on the occultation were written a century earlier in the tenth century, before another prominent Shi’ite scholar, Shaykh al-Tusi, who had studied with Shaykh al-Mufid, had produced the most remarkable and erudite works on the doctrine of the Hidden Imam. On comparison, as we concluded, there were differences in the details provided by the latter scholars on the doctrine of occultation and the future coming of the Islamic savior, al-Mahdi. Of course, we agreed that one can detect some kind of evolution in the doctrine from a simple belief about the last Imam and the doctrine that he was the promised messianic Imam, al-Mahdi, of the Muslim community.

AT: Was this conclusion derived in conversation with Ayatollah Milani?

AS: No, this is Sayyid Fazel al-Milani, the grandson of Ayatollah Milani, not the Ayatollah himself. You could discuss such matters with his grandson, not the Ayatollah himself. He knew the modern world and in Najaf he was exposed to one of the most atrocious period of Iraq under Saddam. Although Sayyid Fazel is a traditional scholar, he is in England and continues to teach in the Islamic College in London. But even with this enlightened contemporary scholar one could not raise all controversial issues. I searched for the answers myself, and realized that without deconstructing the texts it was not possible to speak about the gradual development of the belief becoming part of the complicated doctrine of the creed. For example, al-Ash’ari in his book on Muslim sects entitled Maqalat al-Islamiyyin does not deal with the doctrine of the future coming of the messianic Imam to save the community from perdition. He was writing in the tenth century, and in the tenth century there was a limit to what the Sunnis believed and knew about other sects in that period. Likewise, if a Shi’ite author wrote about the Sunnis, then, as a methodological requirement, I would ascribe the belief in the tenth century to what the Shi’a knew about the Sunnis. In other words, no text is free of some kind of pre-understanding that is provided by other sources to that understanding. I would use Sunni sources to speak about Sunnism, by the way, so that I would not antagonize them. If one investigates the traditions in Imam Bukhari’s compilation – the traditions that were compiled in the tenth century, towards the end of the ninth century – one expects to find in Bukhari the summing up of what the Sunnis believed in tenth century. My interlocutors finally understood my project and they tacitly acknowledged the “process” of systematization of the Shi’ite or Sunnite creed. To be sure, Bukhari could not ignore what the Sunnis believed and knew about their own creed in that century. Could that scenario not repeat for the Shia in the ninth or tenth centuries?

Replicating what I had concluded about Imam Bukhari’s compilation, I could now raise the question about the Shi’ite compilations, keeping in mind the rule about chronology of the written sources in Shi’ism. If we examine the traditions in the earliest compilation of the Shi’ite traditionist, Shaykh Kulayni (d. 941), on the subject of the occultation of the last Imam and then compare these traditions with the next person writing on the subject, Kulayni’s disciple, al-Nu’mani, we discover more detailed and different explanation of the two forms of occultation, shorter and longer, that is absent in Kulayni’s compilation. When we investigate the sources chronologically, then it was not difficult to speak about the “evolution” of the belief to become a complex theological doctrine in later works. One could not get a full picture of what people believed unless there was some observable, objective source for it. My overall conclusion, to which my teachers more or less agreed, was that the university teaches a methodology that requires the researcher to contextualize the texts historically to detect different trends in defending and propounding one’s creed as the only “true” creed.

AT: Did you publish your doctoral research subsequently?

AS: Yes, I published it after a thorough revision that was required because doctoral dissertation is not a book. It took me almost one year to transform my dissertation to a monograph on the subject of Islamic Messianism. It was published in 1980.

AT: Was it the SUNY Press?

AS: Yes, it was. My colleagues used to joke about this by pointing out: “SUNY [suuni] Press, eh?” After all, as they pointed out, it was only SUNY press that could publish that book, since no Shi’ite press would have published that study. I am not against Shi’ite or Sunni schools of thought. This study on Islamic Messianism, if you read it, you will quickly realize that I have not been disrespectful to the Shi’ite school of thought. As a scholar, I have upheld a responsibility with necessary integrity that one cannot hide the evidence that one finds in the research.

PART-3

Western Study of Islam and Teaching in the East

AT: But you say initially you were a little bit uneasy or worried that your scholarship was encroaching upon the boundaries between “insider” and “outsider” dichotomy.

AS: Yes, I am worried about the difference in the two types of discourse on religion that I had mastered in my research, teaching, and scholarship. Even now, I am fully aware that the dichotomy between an “insider” and “outsider” that is created necessarily by the academia is not acceptable to the faith community. Of course, as years went by in teaching and writing I learnt the importance of the academic distinction and kept it at all times as a methodological guide to my work. In the close to half a century in dealing with the scholarship and training graduate students, I had come to appreciate my academic commitment to research and writing. In fact, I liked the “detached” attitude to teaching Islam. The transformation from “my” to “Muslim” faith made me even more courageous to decipher the author’s intention and preunderstanding, not only in the classical scholarship; but also in the modern, so-called “objective” scholarship in the universities around the world. Islamic studies in the West suffer from serious “subjectivism” and “authorial pretext”. Even now it is only Islamic studies that is treated that way. The demand for honesty in the study of the “other” (here, Islam and Muslims) has reached a level of academic “hypocrisy” that speaks volumes about the intention of not only non-Muslim interpreters of Islam; it also implicates scholars from “inside” who appear in “secular” garb and who engage in “insider’s” discourse. The problem can be traced back to centuries of epistemically questionable conclusions that frequently appear in the name of “Islamic philosophy” or “Islamic mysticism.” It is not an exaggeration to point out that there is a “crisis” in the way Islamic studies has been politicized after 9/11 and the way “representational” discourse on Islamic studies has been institutionalized and legitimized in the academia. Compare this with Christian and Jewish, on even Buddhist studies, and notice the ill fate of Islamic studies all over the western academia.

AT: In relation to this, I know you are talking about your own pedagogy to which we want to dedicate a good portion here, so we will get back to that. But in that regard how do you see the kind of models that seek to bring seminary education to the level of academically oriented education together? We have a lot of Christian colleges. Similarly, we have a lot of Muslim organizations and educational establishments, especially in the Western hemisphere, trying to bring together a liberal arts education and religious education. Do you think one ends up sacrificing the other?

AS: Let me begin by saying that I have started teaching methodology courses in Iran, in the seminary. That has opened a new chapter in the seminary approach to the academic study of Islam, Islamic theology, Islamic jurisprudence, and Islamic ethics. In the four decades of my role as a university teacher and researcher, I have been able to lay down the foundation of critical source studies in many places in the Muslim world. My success can be partly attributed to the respect that I have earned in those countries regarding my honesty in transparently laying down exactly what I am doing.

I am not hiding anything about my research or academic approach anymore; that is one thing that I have been able to achieve. I have adopted a simple policy vis a vis my audience: “If you can tolerate me, then I will tell you; if you do not want to hear me, then I will go away! Don’t invite me if you cannot withstand my approach to Islamic knowledge and practice.” That is my teaching policy. Qom has published my lectures on methodology in Persian which are being used as a textbook. In Qom, among the traditional scholars, I have now given lectures about human rights, religious pluralism and the academic methodology I apply in my studies in Islamic law and ethics. I have lectured on bioethics and the methodology I use. And Iran has published my studies in those feilds in Persian. Since I have been teaching in Persian, Iran has published my lectures and my specific take on Islamic texts as a guide to teach new students of seminary – the modern methodology.

AT: Is this the same methodology that you teach here?

AS: Yes, it is a Western methodology – methods of studying religion academically. I have not shied away from revealing the social scientific and humanistic studies of religion. It is possible to attribute to my method an appellation that is becoming common to generate doubts about the aims of critical religious scholarship. This is commonly identified as “neo-orientalism” or “orientalism.” However, I would like to point out that “orientalism”, in my opinion, is not all negative. There are also good aspects of orientalist scholarship, because these orientalists were the ones who studied the classical texts methodically and taught us to read these in their cultural context to analyze them. Now, it is possible that we might not draw the same conclusions as they do, and that we might have additional sources to examine in order to interpret the culture that we know more intimately. In other words, the culture of the book is left to us for interpretation, even when the textual-historical method is correct as far as its application is concerned. The application deals with analysis of terms, their etymological/lexical uses in the context of sociology of knowledge; the predominant epistemology, and the methods that reveal the ways information about a period that is under investigation was gathered and disseminated. All these are important questions for us, otherwise we would be writing very poor histories. We would certainly be writing poorly researched and compiled knowledge about Muslim social-political contexts that had impacted upon the history of religious ideas.

Let me emphasize that the process of my being accepted in the traditional centers of Islamic learning was gradual, and it took the traditional authorities even longer to afford me an opportunity to teach and lecture on these controversial topics about academic treatment of Islam in their traditional institutions. Now I am one of their sought after teachers, one of their academic consultants in Qom or in Najaf. I spent time in the University of Kufa, in Najaf, where I taught methodology in Kulliyat al-Fiqh (College of Islamic Jurisprudence), which is actually an extension of the hawza, the hawza ‘ilmiyya – the seminary. I also lectured to the students of traditional learning in Kulliyat Shaykh Tusi (Shaykh Tusi College), which is the religious college geared towards understanding new methods of studying religion. So there is already a movement that is tolerating academic studies on Islam. It is still too soon for me to say if the traditional students have imbued new methodologies. I have to read the new books and articles they are writing and publishing to enable me to judge the quality of their studies. As I speak to you, seminarian authors are busy advocating a doctrinal position that is theologically sound. The dominating culture in these places is still defensive rather than liberal. It is more apologetics than doing a solid piece of critical research to explain the incongruities in religious texts.

AT: It would appear that the final outcome of this new experimentation in academic methodology is still inconclusive.

AS: It is possible to generalize the problem all over the Muslim world. There is still hesitation in submitting the religious sources to the academic scrutiny. The situation in the Sunni world is no different. I think it is gradually dawning upon some Sunni scholars, more in Iraq and Egypt, but I think also in other Muslim countries that modern methodologies cannot be ignored if Muslim studies undertaken in Muslim majority institutions are to be taken seriously in the Western academia. Take the case of my book, The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism. It is now available in Persian and Indonesian. It still awaits to be translated in Arabic, which is going to be published in Cairo under the sponsorship of IIIT in Herndon, Virginia. By the way, Indonesia accepts modern studies on Islam wholeheartedly by translating them. This shows the intellectual maturity of the Indonesian scholars in dealing with the academic studies of Islam. All my published works have been translated in Indonesian language. Some scholars in Turkey were trying to make some of my works available in Turkish. I am not sure if the project has seen the day.

Scholarship Interests and the Field of Religious Studies

AT: Let me raise a related question. Your work on The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism was published in 2002. You published your research on Islamic Messianism in 1980. Your next book is on freedom of religion with your UVA colleagues on human rights. It naturally raises the question: After your doctoral studies in the University of Toronto in 1976, you started your tenure-track job as assistant professor at the University of Virginia and continued there until 2011 for 35 years. So as a young scholar, soon after your publication in Shi’ite studies, you started to focus on the issue of human rights, democracy and Islam. I am interested to know what prompted the change in your interests from classical to the contemporary issues.

AS: My research interests in Shi’ite studies continued for a while. My next major project was on: The Just Ruler in Shiite Islam. This study marked the interim stage in my research. The subject of the Just Ruler (al-sultan al-‘adil) was actually a sequel to my first book on al-Mahdi. The main research question in this book was: How did the Shi’ite community cope with the absence of the last Imam during the period of complete occultation? How did Ayatollah Khomeini become the leader and founder of the Islamic republic of Iran? I started working on the Khomeini-concept, the idea that during the absence of the last Imam the qualified jurist was the guardian of the community (wilayat- al-faqih). This research took me on a long journey through the juridical heritage of Shi’ite school of thought.

AT: Indeed, the title of the 1988 book is The Just Ruler in Shiite Islam published by the Oxford University Press.

AS: This is the study about the history of the comprehensive authority of the jurist in Shi’ite jurisprudence during the period of occultation of the last Imam, in the 10th and 11th centuries until the modern period of Ayatollah Khomeini’s independent ruling about the right and responsibility of the qualified Shi’ite jurist to assume a constitutionally enacted position of the “guardianship of the jurist” in Iran.

Let me now come to your specific question about my transition from classical to contemporary issues in Islamic studies. Like any graduate of the department of the Near East or Middle East studies, I was trained as a historian in the University of Toronto. Most of the professors in this department with whom I studied were historians, not theologians. There were no legal experts teaching me. I got that training from Iran, Iraq, and wherever I went in the Muslim world. I studied jurisprudence with a number of Iranian, Iraqi, and Jordanian scholars. I can say that while I studied Islamic jurisprudence, my project was to understand how theological doctrines influenced the study of applied jurisprudence and its methodology.

AT: This is very interesting. Does it mean that you were a historian of the Middle East studies when you were offered a position in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia in 1976?

AS: Yes and no. In the Department of Religious Studies I was supposed to teach courses on Islamic religion. My first task was to equip myself with the methodologies that were prevalent in the academic study of religion. For the first three years I trained myself to teach courses in religion, theologies, religious practice, mysticism, and so on. I was primarily a historian, and now I began to relate beliefs and doctrines chronologically to the events in Islamic history. It was broadening my work on Islamic idea of future savior – Al-Mahdi. I began to pay attention to the sociology of religion, to cultural anthropology and the psychology of religion. These were all new but very interesting fields for my own development as a historian of religion. As an only one professor of Islamic studies at University of Virginia I was in demand to interpret Islam’s relationship to human rights and democracy. I was also called upon to lecture in courses on Islamic law, Islamic business, Islam and medicine, and so on. UVA supported my research and my scholarly interests. For me Islamic studies now went beyond the classical Shi’ite or Sunni studies. The demands on me provided me opportunities to expand my narrow academic specialization. It is for this reason that since 1988, I have rarely published any major work in Shi’ite studies.

AT: Is this what you meant when earlier you said you were trained in classical studies which led your way to the modern topics in human rights, democracy and bioethics, which are in some way related to legal schools of Islamic practice?

AS: Yes, indeed interpretive jurisprudence (fiqh and usul al-fiqh) was at the heart of my studies. However, my academic studies are geared towards relating historical events to specific judicial decisions (fatawa) from the juridical sources of Islam. This inquiry constitutes my essential research interest even today. I am still looking for ways to demonstrate how juridical studies can benefit from history.

AT: This is what you have demonstrated in your study on The Just Ruler in Shi’ite Islam, where law, ethics, and society intersect.

AS: That is correct. History and jurisprudence, history and literature, religion and literature, religion and politics, law and ethics, have remained my focus in Islamic studies. Hence, in each of my published work, I try to develop the connection and demonstrate the need for interdisciplinary approach to the academic study of Islam. In this connection it is important to point out our collegial work in UVA which prompted serious interest in my future studies. My colleagues at UVA started working on the Qur’an and freedom of religion. I had never thought about such a trajectory. So I too started examining the Qur’an for those themes. My incorrect “insider’s” assumption about the Qur’an was that Islamic revelation would obviously only tolerate Islam as the absolute truth from God. This was the residue of my belief system that would not let me see the Qur’an except as an exclusionary text. As a believer, deep in my heart, I entertained the belief that Islam is the best religion. One day everyone will become Muslim. That was my childhood image of my religion.

I had never thought I would be teaching Islam as one of the world religions in Department of Religious Studies, which is strong in Christian and Jewish studies. I was the only person teaching Islam. The department was strong in its offerings in other eastern traditions like Buddhism and Hinduism. Islam, released from its confines in Near Eastern studies, was a “newcomer” in religious studies. So I had to relate my work to my colleagues in religion. I could have isolated myself and become completely separated as I used to hear in some institutions the teachers of Islam, mostly graduates of Near Eastern Civilizations and Cultures, were not talking to the colleagues in Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, African religions. I could have followed that path; I could have remained totally submerged into Islamic studies and Arabic studies. But I chose the other path. I convinced myself that I needed to sit in conversation with my colleagues.

So I found the common ground in freedom of religion and conflict of cultures in human rights. I had never paid attention to the jargon that was common to these scholars of human rights or freedom of religion that I started picking up in conversations with my colleagues. Professor David Little was a sociologist of religion, quite well-known in his own field of comparative ethics and human rights. Professor Jim Childress was working on moral reasoning and in bioethics. I started having conversations with him on common ethical issues, not only on the organ donations but in search of principles of bioethics in Islam. How was Islamic law responding to the modern medical questions? Was it possible to teach Islamic ethics? What direction would ethics take in Islam: will it be philosophical? Theological? Religious? All these questions became part of my search in bioethics and other comparative ethics concepts. Since I was the only one who taught Islam, I had to pay attention to the broader implications of Islamic religious thought. This pressure functioned as a constructive and challenging motive for broadening my education in the context of the Department of Religious Studies at UVA. I must confess that the relevance of religion in the Muslim communities in North America was my major research question. I said to myself, “Religion cannot survive without being relevant today!” Humanity was in need of spiritual and moral guidance at all times. If religion cannot speak to modernly educated men and women and guide them to become better persons, then what good is religion for? So I really moved in different areas of the study of religion that had practical application in business, bioethics, social ethics, and personal ethics of modern men and women.

AT: Thanks for your elaboration. However, it raises two related questions: The first question is the context and setting in which you are engaging your scholarship. The second question is regarding your setting in the community. As a Muslim you lived as a member of a minority in Charlottesville where University of Virginia is located. Consequently, some of the research questions were probably becoming relevant for the believers. This is the first context to which you could speak. The second context is obviously the socio-political one within which Islam as a religion was being debated. Maybe some of the conversations about human rights and Islam were a little bit intimidating and appeared aggressive to the religious people in the community. From the beginning of our conversation you have emphasized the ways in which these contexts influenced your research projects. Could you speak to these briefly?

AS: Yes, I think University of Virginia was a gold mine for me to understand academic study of religion. First, that which characterized the Department of Religious Studies at University of Virginia in the 1970s and 1980s was that the department expected that religious traditions taught in religious studies would be best taught by those who were in some ways “insider” academicians. This meant that these teachers fully appreciated religious practice, even if they remained non-practicing themselves. Second, it was also regarded as a plus, if the teacher of a specific tradition was connected culturally/religiously to her own community. Accordingly, we had Jewish rabbis teaching Judaism, we had Catholic priests teaching Catholicism, we had ordained ministers teaching Christianity. A very good friend of mine, Professor Fred Denny, who was Christian, taught Islam, up to that point. He was the graduate of University of Chicago Divinity School. Most of the faculty in Religious Studies had either studied at Yale, Princeton, or Harvard Divinity Schools. In other words, they were trained not only in the modern methodologies; but also in intellectual appreciation of the traditions they specialized in. Even in the relatively non-confessional domain of Religion and Literature the department had attracted Professor Nathan Scott, one of the most prominent authors in the field, who was also a member of Episcopalian church. He was teaching at the University of Chicago before he joined UVA. In cultural anthropology we had another internationally known Chicago professor, Victor Turner, with whom a number of our graduate students in the History of Religions took courses. These are only some of the important names connected with the University of Virginia.

I joined UVA, as a young assistant professor, who was now searching for different mentors in religious studies – quite different from my professors in University of Toronto, and was intending to create my own niche in research and interpretation of Islam. I was like a fully winged bird that could fly off the safety of the nest of University of Toronto and could now venture to sit in any company of scholars I chose, because I was a full-fledged member of the academic community. That parallel with the bird flying off from the security of its nest is very important to keep in mind. I felt I had the freedom to do anything I wanted even when faced with challenges in my transition from a historian of religious ideas to a scholar in need of an anchorage in religious studies. For me to search for commonalities and common ground in conversation, if not agreement and differentiation at the academic level, it was critical to find my own calling in academia. Obviously, in academia you could not afford to remain isolated. Isolation would have been the stifling of my own potentials in learning from others, including my students.

I had come to UVA for one year in 1976 as a visiting professor to replace a colleague on research leave. But my training in languages and history landed me in a joint appointment the following year. So in 1977-78 I had a joint appointment in the History Department and French Language and Linguistics at the University of Virginia. The latter department was home to all “oriental” languages in the 1970s where Arabic, Persian, and Urdu were taught, and I taught all three of them. UVA saw me as an academician who represented authentically the field of Middle East and Islamic studies, being thoroughly grounded in Arabic, Persian, Urdu-Hindi, Swahili and other languages spoken in the Muslim world. I had already been exposed to Ottoman Turkish language minimally, mainly because my research was not directly related to Turkey as much as it was connected with India, Iran, and the Arab world.