As medical ethics indisputably needs to consider patients’ religious beliefs and spiritual ideas, one can suggest that hospitals are responsible for not only patients’ rights and dignity, but also for her/his religious concerns and expectations.

The current study titled “The Implementation of the Sharia Law in Medical Practice: A Balance between Medical Ethics and Patients Rights,” is designed shed some light on the patients’ view of the implementation of religious law in Iranian hospitals, specifically, the right of patients to be visited and delivered health services by professionals from the same sex. This protocol is proposed by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of the Islamic Republic of Iran as a response to the increasing demand for implementation of the religious law by Iranian patients.

This research is a cross-sectional study which was conducted at four teaching general hospitals in Tehran, Iran. The data was collected by the means of a questionnaire distributed to 120 women who were admitted to different wards of the hospitals. These women were asked to express their opinion of the implementation the Same Sex Health Care Delivery (SSHCD) system in Iranian hospitals. All analyses were performed with the use of SPSS software, version 16.0.

The results indicate that half of the hospitalized women believed that being visited by a physician from the same gender is necessary who advocated the implementation of SSHCD in a clinical setting; and most of their husbands preferred their wives to be visited exclusively by female physicians.

This study highlights the view of the Iranian patients towards the issue and urges the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of the Islamic Republic of Iran to accelerate the implementation of this law.

SSHCD is what the majority of Iranian patients prefer, and, considering patients’ rights and the medical ethics, it should be implemented by Iranian policy makers.

Spirituality and medical ethics has recently emerged as an important topic in the health care provision and there exists a heated debate surrounding the issue. Medical ethics is in the curricula of virtually all medical schools all around the world. On the other hand, spirituality and religion is considered as an inextricable part of almost all medical codes of ethics. Therefore, one could suggest that patients’ religious ideology and beliefs should be taken into account in any clinical setting (1, 2).

Spirituality is usually defined as the aspect of humanity that refers to the way an individual seeks to follow in life. It is supposed to add meaning and purpose to life, and facilitate the connection with the moment, self expression, and attitude towards other human beings, nature and the sacred (3). Spirituality and religious beliefs have been shown to have an enormous impact on how people can cope with serious illness and life threatening stresses (4, 5). Spirituality if often claimed to give people a certain feeling of wellbeing, improve the quality of life, and provide social support through spiritual social activities (6, 7).

New advances in medical sciences have made it more than obvious that including moral issues in this profession is indispensable. As medical profession deals with individuals’ bodies and lives, it needs to consider morality and dignity of human beings (8). Therefore, medical practice is interlinked with a great deal of responsibility as it deals with human beings’ physical and mental health; consequently, it should take all considerations into account including spirituality and religion (9). In today’s world, medical ethics has been the subject of considerable attention due to the mentioned issues and it is the subject of heated debates. Medical ethics include a set of values and codes which aim to build trust and confidence in physicians, patients, and the society as a whole. A physician’s competence depends not only on his medical knowledge, clinical decision making, and practical skills, but also, on his ideology and practice of medical ethics (10, 11). As one of the four basic principles of modern ethics is respect to patients’ choice in clinical practice, physicians should respect patients’ religious and spiritual choices (12).

Patients are only one side of the interaction in a clinical setting; physicians too, may have religious ideas and beliefs which may influence their practice. The religious ideology and beliefs of physicians can even more complicate the issue when patients’ religious choices come into play (12).

As argued, the concept of morality and medical ethics has become the focus of attention in medical practice, and, its implementation is furiously advocated (13). Therefore, hospitals need to consider all aspects of patient’s rights including the right to be treated based on their religious ideology. In fact, respecting all aspects of patients’ rights such as their participation in decision making, respect for privacy and dignity, and interpersonal relationships are considered intertwined with several different aspects of health care delivery (14).

The U.S. legal system has been pioneer in implementing a robust approach to a health care provision system respecting all aspects of patients’ rights such as their special religious demands, while pursuing excellence in all aspects of health care delivery (15).

In addition to considering moral issues and respecting religious beliefs of patients, public and governmental hospitals need to promote accountability. Respect for patients’ rights and enhanced communication with patients can pave the way for development of moral competence (16). In fact, it is argued that undermining medical and moral accountability in some countries has resulted in patients’ loosing their confidence in the system regarding moral, legal, monetary, and political affairs (17). Moral accountability in governmental hospitals is defined as the extent to which they implement and monitor adhering to moral principles by the authorities and staff (18).

The need for defining a role for religion in human beings’ everyday tasks is not limited to a specific religion, a certain geographical area, or a particular time period in the history. In fact, it can be argued that man has always felt this need all through the human history including the present time. Islam, as both an ideology and a practical way of life, is argued by its followers, to provide solid foundation for different aspects of life (19, 20).

The clinical setting and medical affairs seem to be in priority when implementing the religious law is concerned. Islam treats physicians and health care professional with an utmost dignity. This dramatically increases the physicians’ responsibility. As Islam is all about faith, dignity, honesty, and mutual trust, medical ethics is of paramount importance for Muslims as it needs to protect them from anything that might endanger the Islamic principles (21, 22).

In this study, we aimed to conduct a poll to find out what female Iranian patients think about the implementation of the Same Sex Health Care Delivery system (SSHCD) in accordance with the religious law in a number of teaching general hospitals of Tehran, the capital of Iran. This plan was first proposed by Ministry of Health and Medical Education of the Islamic Republic of Iran due to increasing demand of patients and policy makers, and, consequently, the Supreme Council of SSHCD was established in 1997. The Parliament of the Islamic Republic of Iran passed the bill of this plan in 1998, and, in the same year, it was communicated to all healthcare organizations in Iran. Also, the supplement to this law was approved in 2006 (23). This study is the result of all endeavors to clarify whether the project can be implemented in Iranian hospitals or not, and whether the patients would prefer and embrace it. This project is supposed to encompass all aspects of religious law regarding medical practice including the need for female patients to be visited and cared for, exclusively, by health care providers from the same sex (24, 25). The plan of SSHCD project also includes a different part which is designed to define medical practice codes based on the religious law. This project is supposed to be followed by all medical practitioners practicing in the Islamic Republic of Iran (26).

The first step of the project is intended to separate women and men in hospitals (21). Moreover, physicians should be required to visit patients from the opposite sex only when it is inevitable. This way, any unnecessary contact of the health care provider with the patient from the opposite sex is minimized (24). Finally, physicians’ bedside manner and their conduct toward their patients need to be according to the religious law (22).

Materials and Methods

This research was a cross-sectional, descriptive – analytical study which was conducted at teaching general hospitals in Tehran, Iran. In this study, we chose four hospitals from different neighborhoods of Tehran which were similar in terms of size, number of beds, number of patients admitted during a particular period of time, number of staff, and the health care services delivered. The questionnaires were to be answered anonymously, and, in order to protect their confidentiality, the names of the participating hospitals were not disclosed. The Cochran formula was used to calculate the number of female patients as the research cohort. In each hospital, 30 female patients were selected from different wards using cluster sampling method. The assessment tool was a questionnaire comprised of 18 questions and the questions had a focus on demographic information, the preferred gender of the visiting physician, the importance of being visited by a physician from the same sex, and the most important moral issue they faced during their hospitalization.

Before the commencement of the study, a pilot study was performed to check the reliability of the questionnaire. In order to ensure that, some of the patients were asked to complete the questionnaire randomly two weeks prior to the study. The results obtained from test- retest method were studied and compared with those of the main study. The reliability coefficient for this measurement was relatively high (Cronbach alpha=0.85). Also, the face and coincidental validity were performed. Therefore, it was ensured that the questions of the questionnaire were highly valid.

The questionnaires were distributed among 120 women who were admitted to different wards of the hospitals. Also, we asked the patients to mention their husbands’ opinion about their wives being visited exclusively by female physicians and they were asked to express their opinion about the questions. In order to specify the degree of the agreement the three – level Likert scale was used as “agree”, “Disagree” and “Neutral”. The SPSS software was used, and the descriptive data were prepared. The statistical analysis, Chi-square and Pearson tests were used to analyze the data. As it was difficult to analyze patients’ opinions by direct observation, the attitude was assessed using measurable bits of evidence such as the expression of beliefs and emotions (27).

Result

Most of the patients were 20 – 40 years old, 89% were married and 79.3% were housewives. 30% of them were illiterate and the remaining had high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree or doctorate degree.

60% of the patients lived in the capitals of the provinces and 40% lived in towns and rural areas. The results indicated that most of the hospitalized women’s husbands preferred female physicians to visit their wives. Half of these patients believed being visited by a female physician is necessary. In contrast, 14.8% believed it was not necessary, and 36.5% did not answer this question.

Almost, half of the patients believed that female physicians were available, 37.2% of them expressed that female physicians were not available, and the rest expressed that they had not noticed it. Most of the patients believed that they mostly felt embarrassed when male medical students were present by their bedsides.

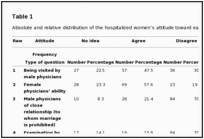

As it is tabulated in table 1, more than half of the hospitalized women believed in the competency of the female physicians and staff and preferred to be visited by them even when male physicians were being present.

Table 1

Absolute and relative distribution of the hospitalized women’s attitude toward each element

Most of the hospitalized women in this study, expressed their concern and dissatisfaction about a number of issues in the questionnaire. Most notably, they felt uncomfortable during physical examinations performed by male medical students. Moreover, they expressed their feeling embarrassed by being visited by male physicians of their own family members or relatives (to whom marriage is prohibited by the religious law). They also opposed to a number of services delivered by male staff, including nursing care, housekeeping services, changing position, being helped with personal activities, urethral catheterization and intramuscular injections. They also were against presence of male medical students during medical examinations, failure of patient’s covering during radiology and laboratory services provided by the technicians or technologists, and the presence of male nurses and staff members of close relationship (to whom marriage is prohibited) during physical examinations. In addition, the majority of the hospitalized women were in favor of the separation of men and women’s rooms at the hospital wards and the presence of a chaperone during medical examinations.

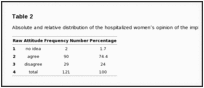

According to table 2, 3/4 of the hospitalized women were in favor of implementation of the SSHCD project in Tehran, Iran. We analyzed the dependency or independency of the variables based on Pearson test, and, it was demonstrated that there was significant relationship between the level of education of the studied women and their opinion about the gender of their physician (P=0.041) and being delivered nursing care by male nurses (P=0.045). Therefore, it can be concluded that more educated patients preferred to be visited by male physicians and received health care by male nurses. Also, there was a significant correlation between the age of the participants and their opinion of the presence of male physicians during physical examinations (P=0.002), being examined by male medical students (P=0.002), and receiving personal services by male hospital staff (P=0.019). Older patients were in favor of being visited by male physician, being examined by male medical students, and receiving personal services by male hospital staff. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the incidence of hospitalization and the patient’s opinion about receiving nursing care provided by male nurses (P=0.04), and sharing their personal private issues with male physicians and other medical staff (P=0.01). It was observed that increased incidence of hospitalization was positively correlated with preferring to receive nursing care by male nurses and the other male medical staffs. There was also considerable correlation between the occupation of patients and their attitude towards the presence of male staff during their examinations by male physicians (P=0.01) and the implementation of adjustment plan. There was also correlation between marital status of the hospitalized women and their attitude toward being examined by male medical students (P=0.025). Thus, the hospitalized women with higher job positions preferred to be examined by male physicians; in other words, woman with higher job positions were not in favor of the implementation of the SSHCD project. Most interestingly, there was a direct relationship between the opinion of the husbands and the patients, and the patients themselves regarding the preferred gender of physicians as well as being examined by male medical students.

Most of the hospitalized women in this study, expressed their concern and dissatisfaction about a number of issues in the questionnaire. Most notably, they felt uncomfortable during physical examinations performed by male medical students. Moreover, they expressed their feeling embarrassed by being visited by male physicians of their own family members or relatives (to whom marriage is prohibited by the religious law). They also opposed to a number of services delivered by male staff, including nursing care, housekeeping services, changing position, being helped with personal activities, urethral catheterization and intramuscular injections. They also were against presence of male medical students during medical examinations, failure of patient’s covering during radiology and laboratory services provided by the technicians or technologists, and the presence of male nurses and staff members of close relationship (to whom marriage is prohibited) during physical examinations. In addition, the majority of the hospitalized women were in favor of the separation of men and women’s rooms at the hospital wards and the presence of a chaperone during medical examinations.

According to table 2, 3/4 of the hospitalized women were in favor of implementation of the SSHCD project in Tehran, Iran. We analyzed the dependency or independency of the variables based on Pearson test, and, it was demonstrated that there was significant relationship between the level of education of the studied women and their opinion about the gender of their physician (P=0.041) and being delivered nursing care by male nurses (P=0.045). Therefore, it can be concluded that more educated patients preferred to be visited by male physicians and received health care by male nurses. Also, there was a significant correlation between the age of the participants and their opinion of the presence of male physicians during physical examinations (P=0.002), being examined by male medical students (P=0.002), and receiving personal services by male hospital staff (P=0.019). Older patients were in favor of being visited by male physician, being examined by male medical students, and receiving personal services by male hospital staff. Moreover, there was a significant correlation between the incidence of hospitalization and the patient’s opinion about receiving nursing care provided by male nurses (P=0.04), and sharing their personal private issues with male physicians and other medical staff (P=0.01). It was observed that increased incidence of hospitalization was positively correlated with preferring to receive nursing care by male nurses and the other male medical staffs. There was also considerable correlation between the occupation of patients and their attitude towards the presence of male staff during their examinations by male physicians (P=0.01) and the implementation of adjustment plan. There was also correlation between marital status of the hospitalized women and their attitude toward being examined by male medical students (P=0.025). Thus, the hospitalized women with higher job positions preferred to be examined by male physicians; in other words, woman with higher job positions were not in favor of the implementation of the SSHCD project. Most interestingly, there was a direct relationship between the opinion of the husbands and the patients, and the patients themselves regarding the preferred gender of physicians as well as being examined by male medical students.

Table 2

Absolute and relative distribution of the hospitalized women’s opinion of the implementation of the SSHCD

Discussion

The current study has several unique features. Firstly, it had a focus on SSHCD according to the religious law from a different point of view which is based on medical ethics and patients’ rights. Secondly, this study is one of the few studies conducted on the need for implementation of the SSHCD according to the free will and respect to the choice of Iranian female patients and their family. Thirdly, in this article, the researchers analyzed the demographic characteristics of the hospitalized women (such as age, education, occupation, the incidence of admission to hospitals, marital status and the opinion of their husbands) with regard to the implementation of the SSHCD.

Approximately, half of the hospitalized women believed it necessary to be visited by female health care professionals and they considered it as their indisputable right. Zare Dehabadi has suggested that patient’s rights to choose their physician is in accordance with the WHO declaration and that of the World Medical Association. This is also considered in patient’s rights charters in Malaysia, New Zealand, and Slovakia (28).

Waseem et al. have analyzed several points regarding patients’ preferences for the gender of their health care deliverer. Among the study subjects, 80 percent of the women preferred a female doctor, and when it came to the choice between more experienced and female physicians, none of them chose the doctor who had more experience. They researchers hypothesized some potential underlying basis for the results and suggested the possible implications. However, several studies conducted on hospitalized women’s opinion about their preferences for the gender of health care deliverers found that characteristics such as interpersonal communication and clinical skills had priority over physician’s gender. Moreover, a significant numbers of patients did not express any preference. The aforementioned results are in congruence with those of the current study (29, 30).

The subject of the gender related issues in medical practice and research has been the subject of considerable amount of debate recently. Sex and gender related laws and regulations do not only affect the patient, but also include the relationship amongst practitioners themselves. Considering the important role it plays in daily activities of medical practitioners and its legal, political, philosophical, and moral consequences, the gender related interpersonal communication issues should be taken into account more seriously (31).

The most frequently expressed concern of the patients in this study was the issue of a male medical student’s being present during physical examinations and ward rounds. The participants also expressed their dissatisfaction with the health care services rendered by male nurses and allied health professionals. Moreover, they were strongly in favor of the separation of female patients’ rooms in hospitals.

It is universally acknowledged that patients and their families should have the right to choose their health care providers (32). Therefore, hospitals bear the responsibility of providing patients with their preferred health care services. These services need to respect patients’ choice of the clothing, head cover or Hijab, and carrying religious relics or other symbolic items, as long as they do not interfere with diagnostic procedures or treatment options. Many even argue that such issues need to have priority over medical procedure with more favorable outcomes. Privacy, confidentiality of clinical information, the presence of a chaperone during clinical examinations, and having the right to be visited and cared for by health care providers of one’s own sex are usually considered as patient’ indisputable rights (33,34). Yarsis Surakarta Hospital in Indonesia that is a private healthcare facility with 219 beds and Zhejiang Woman Hospital in china that was founded in 1951 and fit, the local healthcare demand for women and babies, with nearly 1000 staffs, 750 bed, for women and 250 beds for babies, are examples of the world’s attention to human rights (35, 36).

Although the results of our study clearly demonstrated that most of the hospitalized women were in favor of the implementation of the SSHCD project according to the religious law, one should consider several different factors when its implementation is concerned. Azari argues that one of the most important strategies in this regard is to employ proportionate workforce, especially nursing staff and allied health care professionals (37). Shojaie and Ghofranipour indicated that a conservative and tolerant approach should be considered so that to avoid fierce opposition by those who disagree with this plan, and, also, to prevent extremism. It should be also taken into account that the implementation of the SSHCD requires deep and sincere faith of both policy makers and health care providers, and, the strategy of its implementation must be similar to that of the Islamic ethics. Taking these into consideration, SSHCD seems easy to be implemented and requires sincere faith and dedication (38, 39).

One of the most important limitations of the present study was that it was conducted over a specific time period. It could be argued that an increased duration of the study might have demonstrated different results. Secondly, as all patients were recruited by means of a questionnaire, it is possible that during the information collection process some data are missed. Finally, one could suggest that some other factors influencing health care provision for the hospitalized patients that have not been taken into account in our study. Considering mentioned limitations further studies with a larger cohort and extending over a longer period of time seems to be of great importance before implementation of the SSHCD or any such comprehensive plan at a national scale. It is noteworthy that written informed consent was obtained from all patients and every single aspect of academic honesty has been taken into account to avoid plagiarism, misconduct, data fabrication and / or falsification, and double publication.

Conclusion

Apparently, although a decade is passed since the proposal of the implementation of the SSHCD in Iranian hospitals, Iranian patients and their families are still in favor of its implementation. In fact, the advocacy of its implementation has increased during the recent decade. Moreover, the results of previous studies and those of the present one conclude that not only patients are in favor of the SSHCD project, but also a great majority of health care providers advocate it. As a result, we hope that a new common issue about patients’ rights and medical ethics has opened. Therefore, the results of this study, in accordance with those of the previous ones, indicate that Iranian health care policy makers need to consider accelerating the implication of the SSHCD plan.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Medical Ethics and History of Medicine Research Center of Tehran University of Medical Sciences as the study could not be conducted without their kind assistance. The current research was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences and the authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

…………………………………………..

References

- Puchalski CM. Spirituality and medicine: curricula in medical education. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21(1):14–18. [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM, McSkimming S. Creating healing environments. Health Prog. 2006;87(3):30–5. [PubMed]

- Puchalski CM, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality spiritual of care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885–907. [PubMed]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Roberts JA, Brown D, Elkins T, Larson DB. Factors influencing views of patients with gynecologic cancer about end – of – life decisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(1):166–72. [PubMed]

- Cohen SR, Mount BM, Tomas JJ, Mount LF. Existential well – being is an important determinant of quality of life. Evidence from the McGill Quality of Life questionnaire. Cancer. 1996;77(3):576–86. [PubMed]

- Burgener SC. Predicting quality of life in caregivers of Alzheimer patients: the role of support from an involvement with the religious community. J Pastoral Care. 1999;53(4):433–46. [PubMed]

- Gambino G, Spagnolo AG. Ethical and juridical foundations of conscientious objection for healthcare workers. Med Etika Bioet. 2002;9(1–2):3–5. [PubMed]

- Ayatollah Amini E. Physician’s ethical and religious jurisprudence. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2009;1(3):1–6. [In Persian]

- Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):612–16. [PubMed]

- Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):502–15. [PubMed]

- Shaw AB. Two challenges to double effect doctrine: euthanasia and abortion. J Med Ethics. 2002;28(2):102–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Horton K, Tschudin V, Forget A. The value of nursing: a literature review. Nurse Ethics. 2007;14(6):716–40. [PubMed]

- Anonymous. Patient Rights Directives. http://www.Fishermanhospital.com (Accessed in 2011).

- Wardle LD. Access and conscience: principles of practical reconciliation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11(10):783–87. [PubMed]

- Danaifard H, Rajabzadeh A, Darvish A. Explaining of Islamic – moral competence and services culture for accountability in general hospitals. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2010;3(4):57–70. [In Persian]

- Aucion P, Heintzman R. The dialectics of accountability for performance in public management reform. In: Peters BG, Savoie DJ, editors. Canadian Centre for Management Development. Governance in the Twenty-first Century: Revitalizing the Public Service. McGill-Queens Press – MQUP; 2000.

- March JG, Olsen JP. Democratic governance. In: Shapira Z, editor. Organizational Decision Making. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1977.

- Maloob M. In: Man and Religions. Tavakoli M, translator. Tehran: Ney Publication; 2005. [In Persian]

- Reyshahri M. Medical Narrations Thesis. Tehran: Dar – Ol – Hadis Publication; 2005. [In Persian]

- Tavakoli Bazaz J. The Adjustments Plan: Necessities and Barriers. Abstract Book of the 1st Congress of the Adjustment of Medical Affairs with Holy Canons of Islam. Ministry of Health; Tehran. 1996. [In Persian]

- Isfahani MM, Najafi Larijani H. Necessary Approved Characteristics for Medical Profession Concessionaires. Abstract Book of Concessionaires on Medical Ethics. Secretariat of Medical Education Assembly; Tehran. 2005. [In Persian]

- Anonymous. Standard Instruction and Evaluation Criteria of General Hospitals in Iran. Vice Chancellor for Medicine, Ministry of Health, Iran, Tehran; 2007 [In Persian]

- Nick Eghbali A. Necessary Prerequisites for the Implementation of the Adjustment Plan. Abstract Book of the 2nd Congress of Medical Ethics in Iran. Tehran University of Medical Sciences; Iran, Tehran. 2006. [In Persian]

- Saghebi S. Ethics in Medicine. Abstract Book of the 1st Congress of the Adjustment of Medical Affairs with Holy Canons of Islam; Ministry of Health, Tehran. 1996. [In Persian]

- Isfahani MM. Professional Ethics in Health Care Services. Tehran: Iran University of Medical Sciences Publication; 1991. [In Persian]

- Jha V, Bekker HL, Duffy SR, Roberts TE. A systematic review of studies assessing and facilitating attitudes towards professionalism in medicine. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):456–67. [PubMed]

- Zare Dehabadi H. Evaluation of the Management of the Adjustment of Medical and Technical Affairs with Holy Canons of Islam in Teaching Hospitals of Tehran, Shahid Beheshti and Iran Universities of Medical Sciences. Congress of Medical Affairs with the Holy Canons of Islam; Ministry of Health, Tehran. 1996. [In Persian]

- Wasseem M, Ryan M. “Doctor or doctora”: do patients care? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(8):515–7. [PubMed]

- Wasseem M, Miller AJ. Patient requests for a male or female physician. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10(7):429–33. [PubMed]

- Anonymous Sex, gender, and why the differences matter. Am Med Assoc J Ethics. 2008;10(7):427–428. [PubMed]

- Anonymous. Your Rights: The Liberty Guide to Human Rights. http://www.yourrights.org (accessed in 2011)

- Anonymous. Patients Rights. http://www.cannonhospital.org/page_id=97 (accessed in 2011)

- Anonymous. Patient’s Bill of Rights. http://www.patienttalk.info/AHA_patient_bill_ofrights.html (accessed in 2011)

- Anonymous. Yarsis Surakarta Islamic Hospital. http://www.dothealth.com/companydetailsasrx?guid (accessed in 2010)

- Anonymous. Woman’s Hospital School of Medicine Zhejiang University. http://www.Womenhospital.Cn/dtdocs/chinese/yygk/yygk_index.aspx (accessed in 2010)

- Azari S. Implementation of the Plan of Adjustment of Medical Affairs with the Holy Canons of Islam in clinical wards of teaching hospitals of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Tehran: School of Nursing, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 1996–1997. [In Persian]

- Shojaie A. A Report of Implementation of Adjustment Plan in the Medical Centers of Army of the Guards of the Islamic Revolution. Abstract Book of the 1st Congress of the Adjustment of Medical Affairs with the Holy Canons of Islam; Tehran. 1996. [In Persian]

39. Ghofranipour F. Planning the Stage of Complying Medical Affairs with the Holy Canons. Abstract Book of the 1st Ethics in Iran. Tehran University of Medical Sciences; Iran, Tehran. 2007. [In Persian]

Bibliographic Information

Title: The Implementation of the Sharia Law in Medical Practice: A Balance between Medical Ethics and Patients Rights

Author: Hussein Dargahi

Published in: J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2011; 4: 7

Language: English

Length: 10 pages

Ijtihad Network Being Wise and Faithful Muslim in the Contemporary World

Ijtihad Network Being Wise and Faithful Muslim in the Contemporary World